Montessori's Discovery of the 'Normalized' Child

Hiding in plain sight || Montessori Series 1/5 ||

“It took time for me to convince myself that this was not an illusion. After each new experience proving such a truth, I said to myself, “I won’t believe yet, I’ll believe it next time.” Thus, for a long time I remained incredulous, and at the same time deeply stirred and anxious. How many times did I not reprove the children’s teacher when she told me what the children had done of themselves?

“The only thing that impresses me is truth” I would reply severely.

And I remember that the teacher answered, without taking offense, and often moved to tears: “You are right. When I see such things, I think it must be the holy angels who are inspiring these children.” One day, in great emotion, I took my heart in my two hands as though to encourage it to rise to the heights of faith and I stood respectfully before the children, saying to myself: “Who are you then?” … And holding in my hand the torch of faith, I went on my way.”1

With these words, Maria Montessori set aside all her preconceived notions about what children were like and set out to discover the true nature of the child. What did she discover about children? Why was she convinced that she was right? Welcome to ‘The Parenting Handbook,’ I’m Samantha Joy, and today we’re doing a deep dive into Maria Montessori’s discovery of the ‘normalized’ child.

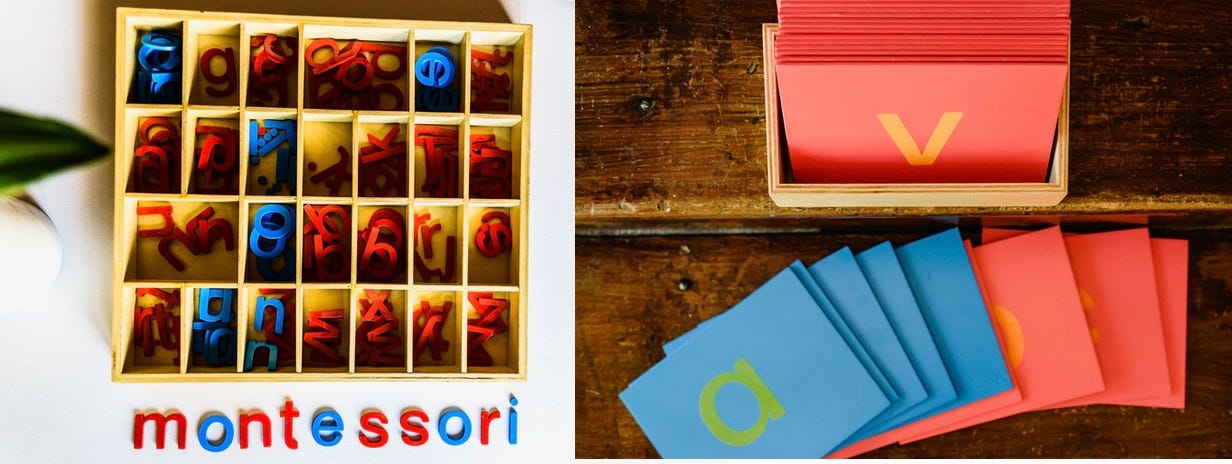

If you spend much time in the world of parenting and educational social media, you may be familiar with the name ‘Montessori.’ Perhaps you’ve seen pictures of the bright and beautifully arranged classrooms with their child-accessible shelves of hands-on materials. Maybe you’ve seen clips of infants learning to drink from glass cups or toddlers learning to put on their coats with a special coat-flip technique. It may seem like this is another flashy trend from social media that will fade with time, but these materials and methods were actually developed by an Italian doctor born over 150 years ago.

Maria Montessori was an Italian doctor, pedagogue, and philosopher who is renowned for her pioneering educational work especially in, what we would call today, Special Education and Early-Childhood Education. Her first work was with children who were cognitively impaired or otherwise considered ‘ineducable’ by society. Through her work, these children eventually went on to take the same tests as mainstream children. Surprisingly, these ‘ineducable’ children passed the tests and did as well as or better than the mainstream children. Most people thought this was nothing short of miraculous. Montessori, however, was disturbed.

If these children, with all of their disadvantages, could do as well as the ‘normal’ children, then weren’t the normal children being held down to an artificially low level? What was going on in mainstream education to stifle children’s potential?

These questions spurred Montessori to dream of one day working with cognitively normal children. While waiting for an opportunity, she returned to university where she studied psychology and anthropology as well as read all of the major works on educational theory. In 1906, the owners of a tenement building in the slums of Rome approached her and asked if she would oversee the care and education of the children living there. These children, between the ages of 2 and 7, were running wild in the tenement building, damaging the property, and being a general nuisance. The owners of the tenement wanted a solution. They had heard of Montessori’s work and thought she would be the right person for the job.

Montessori accepted the position and her first school, known as the Casa dei Bambini or Children’s House, opened on January 6, 1907. She finally had the chance of working with ordinary children. It was here that she first made incredible discoveries that were later repeated with children all over the world. It was here that, over time, she developed her materials and her method. It was here that she made her final conclusion that the true nature of childhood had been hidden and the typical child we see all around us is actually the result of inadequate care and an inadequate environment.

The First School

Montessori believed that the unique environment of the first Casa was part of what made it possible to make these discoveries. The environment, the teacher, and the children were the opposite of what anyone would have chosen as the ideal. This was not a place where anyone would have expected educational miracles or psychological breakthroughs. Yet, if any place existed where the raw abilities of children could be seen, then this would be the place. The children’s success couldn’t be attributed to their parents, their school, or their teacher, it could only belong to them.

First, this was a tenement building in the slums of Rome. The people living there were the poorest of the poor, the lowest strata of society. The children’s parents did not have steady jobs, but were day laborers who might have work one day and none the next. The parents were uneducated and illiterate. The only expenditure allowed for in her appointment was for the same expenses that would qualify as “office” expenses. So, she was able to commission some child-sized furniture for the classroom, but little else. The classroom wasn’t bright and pretty with flowers and decorations like you see in Montessori classrooms today. The materials were not initially arranged on low shelves, but locked away in a cupboard.

And in this room, you had 50-60 children, all between the ages of 2 and 7 years old. They were poor, traumatized, malnourished, shy, and practically abandoned children. Montessori hired the porter’s daughter to be the “teacher” and she provided toys and the same educational materials she had used with the special needs children. She showed the teacher how to present the materials in a specific way, but gave the teacher little direction otherwise.

Even with all of these drawbacks from the ideal environment: the lack of a properly educated teacher, the poor and malnourished state of the children, the lack of culture or support the children received at home, the few supplies, what Montessori did have was the mind of a scientist. She was a keen observer who would notice things about a child’s motivation that others would miss. She had an active mind that looked beneath superficial behaviors in order to discover their causes. She was not satisfied with easy answers or the status quo. She was willing to admit when she was wrong and followed the empirical evidence over any a priori ideas she might have had. She asked the children “Who are you?” and followed the evidence of her eyes to uncover who the children truly were.

The Evidence

Before coming to the final conclusion about the nature of children, Montessori made many smaller discoveries that pointed her to this conclusion. If we trace these discoveries, we can understand the evidence that she accrued and why she came to the conclusion that she did, ultimately deciding whether we agree with her conclusion or not.

First, she saw evidence that children were capable of intense concentration and repetition.

She tells of a 3-year-old child who became interested in one of the materials, the graduated cylinders. These are a series of cylinders that increase in diameter and they each fit into a specific hole in a block designed for the purpose. The goal of the activity is to place each of the cylinders into the appropriately sized hole. Montessori observed this little child calmly working, finding the correct slot for each cylinder and placing it inside. When she finished, she would remove all of the cylinders and begin again. Montessori was incredulous. Who had ever heard of a child who had this much focus and patience?

She wanted to test the limits of this incredible focus, so she gathered the other children together to sing and play games. But, still the child worked without stopping or even noticing the commotion around her. Then, Montessori decided to move the child. She picked her up, chair and all, and the child clung to her graduated cylinders and continued the work even as she was being carried through the air. In the end, Montessori recorded that the child had repeated the work 42 times, despite the noise and distractions in the environment around her. The child then emerged from her work and, rather than being fatigued, had a sense of new energy and serenity.

At first Montessori believed this was an isolated phenomenon. Perhaps this child was simply special. However, the evidence of intense focus and repetition among all the children continued to amass. She observed the children take a deep interest in hygiene activities like washing their hands. They remembered the steps in detail and would repeat the process over and over again with apparent delight.

She observed that the children took special joy in meticulously completing practical activities like dusting. They would dust a table carefully, attending to all the details: the top, the bottom, the sides, the decorative grooves. When they finished, they would then begin again. Each time the child engaged in an activity where they focused intently, they emerged, not fatigued, but with new energy and a sense of satisfaction. She noted in her observations that these periods of intense concentration only occurred when the child had chosen for himself some material that interested him and was given freedom to work with it uninterrupted.

This led to her next discovery: that the children could function well with freedom.

Originally, the learning materials were locked away in a cupboard. The materials would be brought out by the teacher when making presentations or the children would ask for permission to use the materials. One day, the teacher was late and, by accident, the cupboard had been left unlocked. The children, wanting to work, helped themselves to the materials. The teacher, once she arrived, was angry with the children and she told Montessori that this showed that the children had a thieving instinct.

Montessori believed instead that this showed that the children were now familiar enough with the materials and were capable of choosing them independently. She decided to test this theory by putting out all of the materials on low shelves that the children could easily access. As she suspected, the children were capable and independently chose the materials that interested them and concentrated happily on them. Working in freedom was repeated over and over again and the children concentrated and worked without issues even when the teacher stepped out of the room or was absent.

As a consequence of giving the children free choice of the materials, Montessori learned that the materials were not chosen equally. Some were used time and time again, while others gathered dust. Surprisingly, she found that the children did not freely choose to play with the toys.

This was really confusing. One of the hallmarks of childhood is the toys, why wouldn’t they choose to play with the toys? She sought to remedy this by doing more introductions of the toys to the children. She would act very animated and try to engage the children in playing with the toys. The children would show initial interest, but it appeared to be superficial at best. They would never spontaneously choose to play with the toys on their own.

This sparked a whole campaign to rid the environment of things that did not interest the children and fill it instead with the objects that enticed the children to concentrate. This was the beginning of her work in scientifically designing and developing her characteristic materials and led to the vast scope and sequence of materials you see in Montessori classrooms today.

Another shocking discovery was that rewards and punishments had no effect on the children.

She noticed this first with a young boy who she observed sitting at a desk all alone, staring around the room indifferently. He also had a ribbon pinned to his shirt. The teacher informed Montessori that he was sitting all alone because he was being punished. The ribbon was a reward that had been given to another student, but which that student had subsequently discarded and given to the boy who was being punished. With this instance, Montessori saw how both rewards and punishments were not taken very seriously by the students.

This was later confirmed by more extensive experience trying to give the children candies as rewards. This was the most shocking revelation. Who had ever heard of children not caring for sweets? Especially, poor, malnourished children! But, despite all of these expectations, the children would consistently refuse the offer of sweets as rewards or discard them in their aprons indifferently. This was so remarkable, in fact, that visitors to the school would often bring sweets with them in order to see for themselves that the children rejected them. It was hard for anyone to believe, even when confronted with it face to face.

The next discovery was no less surprising. Could you imagine a room filled with 50-60 children being anything but loud and shrill? But, Montessori, again discovered a surprising fact: children were capable and even delighted in creating silence.

She had already observed that the children, when freely choosing their work and allowed to work uninterrupted, were quiet and did not get restless and bother their peers. But the discovery that the children could be completely silent as a matter of choice, and that they could maintain it for long periods was unthinkable.

One day, Montessori brought a baby with her to the classroom. She wanted to make a joke with the children about how quiet and still the baby was. She laughed and called the children’s attention to how quiet the baby was, saying that she didn’t think they could be so quiet. The children didn’t take this as a joke, but instead suddenly got very still. She then remarked how quietly the baby was breathing, saying that the children couldn’t possibly breathe that quietly. The children then began focusing on their breathing and got even quieter.

This exercise in silence was astounding to Montessori and it was repeated again and again without the baby, until finally the exercise became a treasured activity in the classroom. The teacher would stand at the far end of the room and whisper the name of each student in succession calling them to her. They would then tiptoe to her, keenly aware of every noise they made. The amount of patience that the children, especially the last children to be called, had to have would have been considered unthinkable before it was experienced.

Alongside these individual discoveries, a more general trend among the children was becoming apparent. The children were spontaneously forming a character of discipline.

Rewards and punishments had been removed. The children had free access to choose materials to work with and the respect to not be interrupted. With only these conditions, the children worked quietly focused on their tasks for hours each day. They neatly returned their work to the shelves once they finished, as if delighting in order. They just as quietly and happily picked out new work. They listened to the teacher’s instructions and obeyed her commands almost instantly. The teacher even remarked to Dr. Montessori that she had to be careful of how she phrased requests because of how quickly the children would respond.

This, again, was a revelation. Weren’t children supposed to be stubborn and defiant? Weren’t they supposed to be loath to obey the authority of parents and teachers? Weren’t they supposed to delight in disorder and making messes?

But, again and again, Montessori was given evidence of the reverse. Without threats or bribes, the children were spontaneously orderly, obedient, and disciplined. This was true whether the teacher was there or not. The ambassador from Argentina had heard of Montessori’s school and the children’s unbelievable character. He wanted to make a surprise visit, not giving the teacher time to prepare any “trick,” to see what these children were really like.

Unfortunately, the day he came to visit was a holiday and the school was closed. A child in the tenement saw him and told him that it didn’t matter if the school was closed because the porter could unlock it and all the children were at home anyway. With that, the porter was sent for, the school was unlocked and the children all gathered to work without the teacher, much to the ambassador’s amazement.

The final piece of evidence that put Montessori over the edge and made her name and her schools a worldwide sensation was what she coined as the “explosion” into writing.

At this point in time, children didn’t start attending school and learning to read until they were around 6 or 7 years old. At the time, however, intellectuals were pushing the idea that this was still too young and that literacy should wait until children were 8, 9, or even 10 years old. The idea that 3- or 4-year-olds could learn to read was preposterous. Maybe the rare genius who is born once a century could do it, but not the mass population, and certainly not slum children with illiterate parents.

At the insistence of the tenement mothers, Montessori provided the children with two of her most famous literacy materials: the sandpaper letters which children could use to trace the shape of the letters with their fingers, and the moveable alphabet which the children could use to create words with cardboard letters. The children were instructed in how to use the materials and given freedom to practice.

One day, a 4-year-old while playing with chalk, suddenly began to write words. He was so surprised that he exclaimed, “I’ve written! I’ve written!” The other children crowded around to see and were so enthusiastic about his discovery that they wanted to try on their own as well. With this discovery, the children soon began to write all the time. They would write with chalk and with pencils. They would even form letters using bread crumbs at home.

This discovery was the ultimate revelation that alerted Montessori to the idea that children had been misunderstood and artificially held down for millennia. These children clearly had apt minds. They were obviously interested in doing real work. They clearly had a drive to perfection and a will for obedience that was not and could not be forced. These children were like nothing that anyone had ever experienced or heard of before. Yet, as she gained more experience and she trained teachers and started schools all over the world, the same facts presented themselves again and again. Regardless of the race, culture, or the economic status of the children she worked with, a new type of child emerged.

The Integrating Idea

Montessori asserts that, in all the children she worked with, nearly the whole of the characteristics that were thought to make up childhood disappeared. The ‘bad’ characteristics as well as some of the ones that people considered ‘good.’

What emerged instead was one type of child. This conversion, as she called it, happened suddenly like the appearance of baby teeth or when an infant first begins to walk.

Additionally, the conversions only happened when the environment was prepared in a particular way. It had to be prepared with engaging materials that the children could freely choose to work with. The children needed to be given the opportunity to concentrate on their chosen work and the work needed to be appropriate for their cognitive development. Given this freedom in a properly prepared environment, the real normal character of the child would appear. Montessori called these children “normalized,” a term borrowed from her study in anthropology, because the children had been converted from their deviated state of behavior to the normal state, to the state proper for acting in the world.

She describes many examples of these conversions. She speaks of a child who was lost in a fantasy world. He would pretend that all the materials were airplanes or that he was an airplane and would flit around the room in complete disconnection from reality. He would talk loudly and bother the other children.

One day, however, he became interested in the geometrical insets and began to work with them. His fantasies at once disappeared and he instead became interested in the reality around him. Instead of everything being airplanes, he would recognize triangles and trapeziums in his environment. He, who used to be careless and drop things, suddenly became calm and careful in his work. He, who used to be boisterous and bothersome, became quiet and focused on his work.

She tells the story of a sibling pair where the younger brother followed his older brother everywhere. He was almost not a separate individual. Whatever the older brother did, the younger would also have to do. Wherever the older one went, the younger would also go. One day, the younger boy became interested in building the pink tower. He became concentrated on this work and did not worry that he was not in his older brother’s company. From that point forward, he became a true individual and could work independently.

These stories of children conversions abound wherever her environment was reproduced whether in Rome, in New Zealand, in India, or in America. This new, ‘normalized’ child appeared everywhere and everywhere had the same characteristics.

The new child was calm, serene, and focused. He was unafraid and self-confident. He was indefatigable in work and took pleasure in using the maximum effort. He was orderly and meticulous. He was patient and happily obedient. He did not grab toys or materials from other children. He did not quarrel or fight or bother other children. He lost his phobias whether he was afraid of the dark, the water, or a certain animal. The more he learned about reality and the freer he was to exercise his faculties with materials adapted to the purpose, the better his character became.

The question remains, then, why have we never seen this child before? Where do all of the traditional traits of childhood come from? The rowdy child who makes a mess, the anxious child who clings to her parent’s leg, the child who has a temper tantrum and cries over seemingly nothing, the child who lives in a fantasy world of dragons and princesses.

Why are they the common child instead of this serious, calm, joyful worker discovered by Montessori? She believed that these characteristics were deviations, regardless of whether they were considered good or bad by adults. These characteristics appeared or were developed by children as a result of the adult’s blindness and the environment’s impoverishment.

Montessori believed that the child, like man, is an intellectual being. She believed that his cognitive needs were as pressing as, and perhaps even more important than, his physical needs for food and water. She believed that most children were suffering from mental starvation and their attempts to meet their needs were met with misunderstanding and repression from adults.

A strong child might act in self-defense and try to defy the blundering of his parents and teachers and assert his rights. A weaker child might recede into a fantasy world made up of toys and dreams since this is the only place where he is left free from the adult. The weakest child will become submissive and passively resigned to his fate, obeying the adult out of fear. Whatever the form of the child’s reaction, according to Montessori, it is a tragic deviation from the true normal child.

The Call to Action

Montessori believed that this discovery should revolutionize the way we think of children and how we interact with them. It informed her philosophy of education, her ideas on the role of the parent and the educator in the child’s life, as well as the role of the child himself and the environment in his development. She made many other discoveries related to how the child’s mind works and how he learns. She meticulously developed methods and materials that would support a child’s self-development at each stage.

But her most important discovery, the one that informed all the others and made them possible, was her discovery of the ‘normalized’ child.

She believed that adults needed to change their attitudes, their beliefs, and their behaviors in regards to children. If they didn’t, they risked hindering or harming children in their self-creation.

She presents two different visions, one positive and the other negative, for the child and for our future depending on what we do with this new information.

She says, in The Absorbent Mind, “The child, not properly cared for, will take revenge on society through the individual that it forms. The treatment does not foment rebels as it would amongst adults, it forms individuals who are weaker, inferior to what they ought to be; it forms characters that will be an obstacle to the life of the individual, and individuals who will be an obstacle to the progress of civilization.” 2

She believed, as we all do, that children are the future. The kind of future we’ll have depends in large part on the children of today and the kind of care they’re given in order to create the adults and the society of the future. Written shortly after World War II and while seeing Europe split in half by the Iron Curtain, the idea of how to create a better future was heavy on her mind.

Yet, she also presents a positive vision, a vision of the normal development of the child and what it would look like and where it would lead.

She says, “It is as though an arrow had been sent flying from the bow and it goes straight, sure and strong. So does the child proceed along the path of independence. This is normal development: an ever growing and more powerful activity shown along the path that leads to independence.” 3

This strong, self-confident, independent individual is possible in all children, according to Montessori, if only the adults in the child’s life observe his true nature closely and prepare the environment accordingly. Only if they recognize that the child is a mind who must freely work in the world with his hands, can they avoid hindering the child and also provide him the help he needs. If the adult does this, the child will do the rest, and the adult he will create will be a benefit to his own life as well as to civilization at large.

Montessori, Maria. The Secret of Childhood (Montessori series Book 22) (p. 102). Kindle Edition.

Montessori, Maria. The Absorbent Mind (Unabridged Start Publishing LLC) (p. 121). Start Publishing LLC. Kindle Edition.

Montessori, Maria. The Absorbent Mind (Unabridged Start Publishing LLC) (p. 122). Start Publishing LLC. Kindle Edition.

This is so good! I have subscribed and will be also sharing this article with my many parent friends of mine. Thank you for writing this!

As a special needs educator that's also working with regular kids, I am realising more and more that the traditional exam-oriented system does more harm than good and I'm looking out for more alternatives.

Looking forward to reading more in this Substack. Keep up the good work!