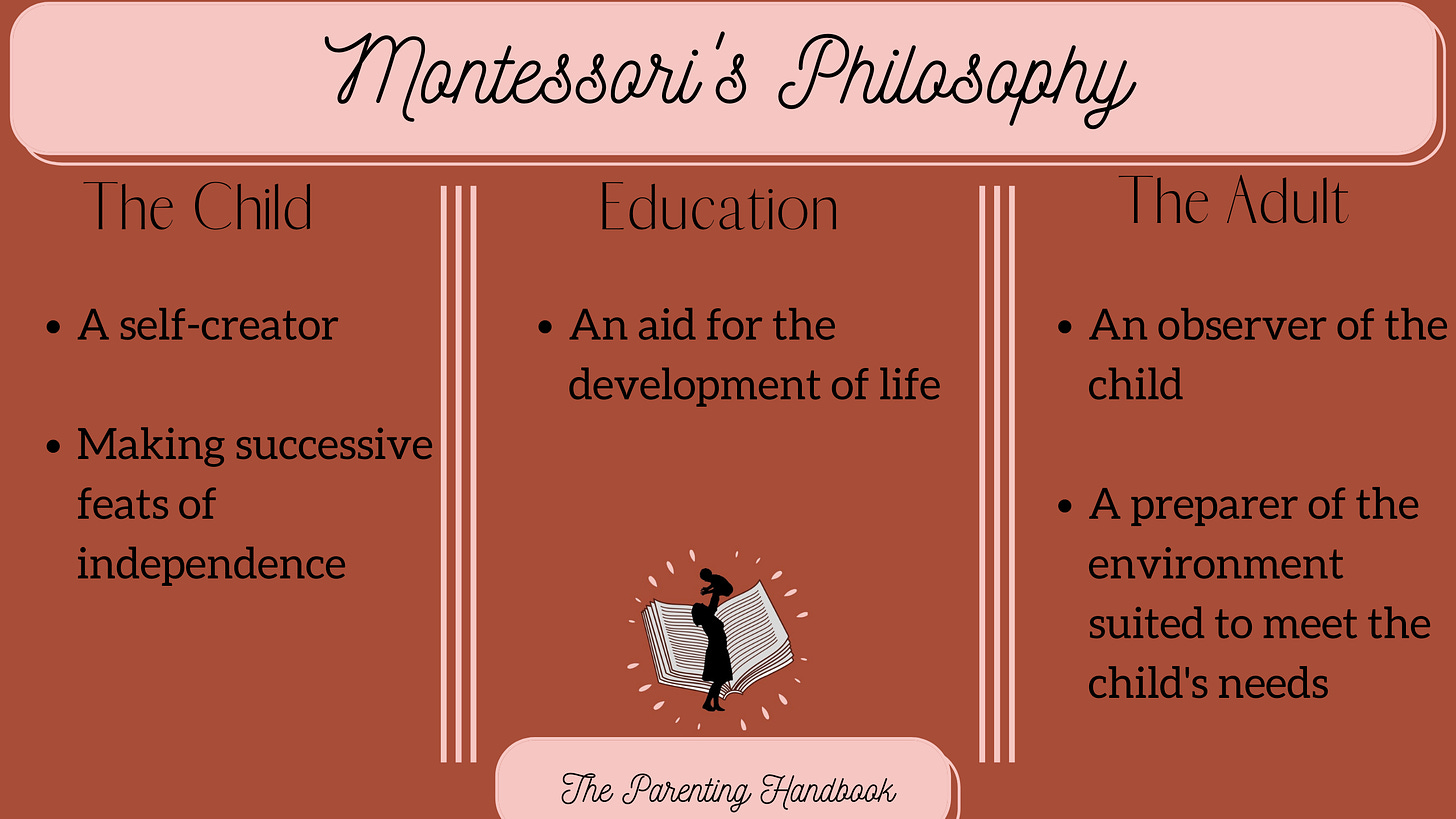

Montessori's Philosophy

What she believes about children, education, and the role of the adult. || Montessori Series 3/5 ||

Click the play button below if you prefer to listen to this article rather than read:

TL;DR:

Maria Montessori thought of herself, first and foremost, as a scientist. She applied her powers of keen observation and careful experimentation to her work, first with developmentally disabled children, then slum children, and eventually children from all cultures, walks of life, and capabilities.

With scrupulous attention to detail and trepidation lest she influence the object of her study and ruin her chance of making an accurate interpretation, she endeavored to observe children as the naturalist observed bees. She awaited the unfolding of the natural child and discovered he was nothing like any child she had observed before. She let go of her expectations of his capabilities and discovered that his mind had powers the adult could hardly imagine.

Montessori believed she uncovered the natural laws governing a child’s development and discovered that he had mental needs from birth. Based on these discoveries, it was clear to Montessori that the traditional ways of interacting with children, educating them, and rearing them were tragically inadequate. It was time to re-think childhood, education, and parenting. It was time to articulate a new philosophy.

There are many philosophical questions that Montessori thought about that I won’t be discussing at length here, though they will appear by implication. Questions about the good life, virtue, the nature of knowledge, the nature of man, and his relationship to others in society. Instead, I want to explore Montessori’s answer to three questions that are of particular interest to educators and parents.

· What is the nature of the child / childhood?

· What is the purpose of education?

· What is the role of the adult in the above?

The Nature of The Child

A Self-Creator

Since the dawn of time, adults watched children become more capable as they grew older. They watched as a weak, mute newborn, unable to meet his barest needs, became a confident toddler exploring the world on his own two feet and communicating with others through his own words. The child had clearly made leaps and bounds in both knowledge and skill over three short years. And yet, during that time he received no direct instruction. No one had—indeed, no one could have—sat down with the child to teach him how to put one foot in front of the other or how to move his tongue and lips to utter his first words.

From this, and other extensive observations of children learning abstract concepts with minimal guidance, Montessori concluded that the child was fundamentally a self-creator. Instead of a passive and receptive vessel that accumulates knowledge handed down to him from superior adults, the child is an active and creative worker who drives his own development. She remarks:

"The child is not an empty being who owes whatever he knows to us who have filled him up with it. No, the child is the builder of man. There is no man existing who has not been formed by the child he once was. In order to form a man great powers are necessary and these powers are possessed only by the child."1

Just as you can’t learn to play the piano through another person’s hands or understand a mathematical formula through another person’s mind, the child cannot develop through anyone else’s work but his own. He must think. He must act. He must work with his hands guided by his mind in order for the knowledge and skills he acquires to truly be his.

According to Montessori, what is true for knowledge of facts and acquisition of skills, is even more apparent in the cultivation of the child’s willpower and the development of his character. ‘Breaking’ the child’s will and dominating him, giving into his every whim, or making all of his decisions for him will not allow the child to develop his will. To develop a proper will, meaning the ability to be neither impulsive nor anxiously dependent on others for decisions, requires that the child independently work to acquire this skill. No one else can do it for him.

For every desirable character trait—whether persistence, ability to concentrate, or patience—the child cannot learn to cultivate it by seeing examples, hearing speeches, or being forced. He must practice. Given abundant opportunities over a long span of time, increasing in scope as he progresses, the child can construct a character that will serve him in any endeavor he embarks on, even into adulthood.

Successive Feats of Independence

Montessori often describes the stages of childhood as successive conquests. They are arduous accomplishments that serve to increase the child’s independence. The infant weans from his mother’s milk and is no longer dependent on her for sole sustenance. The toddler takes his first steps and he is no longer dependent on others to go where he wants. He can defend himself and run away from those who wish to impose their will on him. He can explore the world independently. He understands and says his first words; he can now communicate his thoughts, his objections, his feelings. With each new achievement, he increasingly becomes a competent actor in the world.

Of course, it is no mystery to parents or educators that a child must someday be independent and able to navigate the world; and they implicitly recognize that experiences in childhood prepare a person to take that step. Montessori’s view, though, is explicit and shapes her idea of the purpose of childhood itself.

The child is motivated to work, specifically, to work towards greater and greater degrees of independence. It is more than simply an aftereffect of growth, it is growth. The child’s every act, every decision, every purpose is to increase his independence. And as previously mentioned, this act of development, like all others, must be done alone. No one can do the child’s work for him.

Observing the common behavior of children in this regard, she comments:

"Let us consider the first instinct of the child: he seeks to act alone, i.e., without help from others. His first conscious act of independence is to defend himself from those who try to help him. And in order to act by himself, he tries to make an ever greater effort. If, as many of us think, the best idea of well-being is to sit down, do nothing and let other people work for us then the ideal state would be that of the child before birth."2

Childhood—while filled with joy, new experiences, and impactful relationships—is fundamentally about making a conquest of independence, according to Montessori. Doing things for the child, whether out of an attempt to be helpful or out of frustration at his ineptitude, does more than simply not let the child have his way. It harms his ability to fulfill his goal of becoming independent. It takes away the real human element growing in the child.

"We must understand clearly that when we give freedom and independence to the child, we give freedom to a worker who is impelled to act and who cannot live except by his work and his activity. This is the form of existence for living beings, and as the human being is also living, he also has this tendency. And if we try to stop it then, we produce a degeneration in the individual."3

The Purpose of Education

An Aid for the Development of Life

If it is true that the child fundamentally constructs himself and that his purpose throughout childhood is to become increasingly independent across all domains, then, according to Montessori, the purpose of education needs to be reconsidered in light of this. It cannot be the purpose to fill the child’s empty mind with knowledge, because his mind is not empty and he must be an active participant in the discovery of knowledge. It cannot be the purpose to inculcate virtue through moral lessons or force, because the child gains virtues of character only through independently chosen practice.

Instead, according to Montessori, the purpose of education is to support the child’s development. It is to remove obstacles that hinder his acts of self-creation. It is to clear the path so that the child can successfully be independent. The role of education is not only a negative, however; it is not only the elimination of harm and hinderances. It must also provide the mental nourishment the child needs so that he can make connections, proceed to deeper knowledge, and apply it to his life. She asserts:

"Education is the help we must give to life so that it may develop in the greatness of its powers. To help those great forces which bring the child, inert at birth, unintelligent and unsympathetic, to the greatness of the adult being, this should be the plan of education – to see what help we can give. Before we can give help, we must understand; we must follow the path from childhood to adulthood. If we can understand, we can help and this help must be the plan of our education: to help man to develop not his defects, but his greatness."4

There is much one could say about how this purpose translates into concrete practices in the classroom or at home, but I will leave that for future newsletters. For now, it is important to note that an essential component of fulfilling this new purpose of education is understanding the nature of the child. It means understanding his role as a self-creator. It means understanding the goal of childhood is him achieving the full scope of independence. It means, above all, recognizing that the child has a mind and mental needs from birth.

"If we envisage the baby with a psychic life, with the need to develop its consciousness by putting itself into active relation to the world about it, the image that appears to us is impressive. We see a soul, imprisoned in darkness, striving to come to the light, to come to birth, to grow at the expense of an environment that has not been prepared for such a grandiose event. We find ourselves in the presence of a soul engaged in this difficult task, and we do not know how to help it; we may even hinder it."5

The child needs ‘mental food’ nearly as much as he needs physical food, according to Montessori. It is the job of education to provide the mental food that enables the child’s optimal development. Montessori was passionate about the need for a scientific pedagogy. An educational plan based on the natural laws of a child’s development, a plan steeped in observation and experimentation. She believed there was only one proper method of education, the method that used the child’s nature as the standard and his development as the aim. She stresses:

"There must be there can be only one method of education. The method which helps the natural laws of growth and of development, alike for all. This is not an idea; it is a fact, an evident fact and it shows that it cannot be a philosopher or a thinker to dictate this or that method of education. The only one who can dictate the method is nature itself which has established certain laws, which has infused certain needs into the growing being. It is the aim of satisfying these needs, seconding these laws, which must dictate the method of education; not the more or less brilliant ideas of a philosopher."6

The Role of the Adult

An Observer of the Child

Just as the purpose of education changes with the newfound understanding of the child’s nature, the role of the adult in the child’s life changes as well. No longer is the adult to be thought of as the creator of the child, the child constructs himself: mind, will, and character. No longer is the adult to be thought of as the superior being who must set an example to the child lest he be led astray, the child does not learn through examples, but by doing. Instead, the adult walks alongside the child, a helper, but not the creator, of his life. Speaking of the authority of parents, she remarks:

"Recognizing the merits of the child does not diminish the authority of the father and the mother for when they come to realize that they are not the constructors, but merely the helpers of this construction, then they will be able to do their duty better; they will help the child with a greater vision. Only if this help is well given will the child achieve a good construction, not otherwise. So the authority of parenthood is not based upon an independent loftiness but upon the help that is given to the child. Parents have no authority other than that."7

The first important task of the adult, whether parent or teacher, is to observe the child and to wait for him to reveal his nature. The adult must not watch with the prejudices of old, anticipating the child’s errors, frailties, or vices that the world typically expects. Instead, she implores adults to watch the child with his true nature in mind. It is essential, first, that the adult learn about the child, his needs, and the laws governing his development. Only then can the adult offer the truly needed help. This type of observation is slow, careful to not disturb or influence the inner workings of the child.

She also urges the adult to view the child in a new light. The child should be seen with admiration for his effortful progress. The adult should watch for his conquests of independence with breathless anticipation, celebrating with him each new victory. Speaking of the process of becoming this new kind of adult, a teacher specifically, Montessori says:

"When she feels herself, aflame with interest, "seeing" the spiritual phenomena of the child, and experiences a serene joy and an insatiable eagerness in observing them, then she will know that she is "initiated." Then she will begin to become a "teacher."8

A Preparer of the Environment

According to Montessori, the environment that the child finds himself in is of the utmost importance for his development. If the environment does not contain the mental stimulation the child needs, if it does not allow him to reach success independently, then the child will suffer from its lack. He will develop into a lesser version of his potential, with defects in his mind and character.

The child, however, is not conscious of his needs, much less able to communicate them, and even less able to meet them on his own. It is the role of the adult to know his needs and to be the intermediary between the child and the environment. The child builds his mind and character through independent work in the environment. The first thing, then, that the adult must do is remove obstacles to freedom from the child’s environment.

This often translates to adapting the home or school into a place where the child has independent access to the things that he needs in order to be successful. A stool to reach the sink so that he may wash his own hands, a mirror and small hairbrush so that he may independently care for his hair, a set of kitchen utensils so that he may prepare his own meals, proportinately sized furniture so he can relax and work in comfort, etc.

The child, though, needs more than physical food and more than the tools for practical life in order to develop. He also needs mental nourishment. It is the role of the adult to acquire the materials and organize the home or classroom to meet the needs of the child. Rather than using the materials as a way to “test” or “gauge” a child’s understanding, it is the adult’s job to “test” or “judge” the materials by the response they produce in the child. Because the child builds himself through concentrated work, the materials are judged by their ability to induce an intense interest in the child, causing him to concentrate for long periods of time and to repeat exercises with the materials indefinitely.

Through this whole process of connecting the child to a rich and engaging environment, it is important that the adult respect the child and not interrupt him whenever he is engaged in intelligent work. This is because it is through this outward process of work that the child’s internal progress of building his mind is made. The goal, however, is deeper than the acquisition of particular knowledge or the cultivation of specific skills. The goal is that the child constructs man.

"Our care of the child should be governed, not by the desire "to make him learn things," but by the endeavor always to keep burning within him that light which is called the intelligence. If to this end we must consecrate ourselves as did the vestals of old, it will be a work worthy of so great a result."9

Maria Montessori made countless discoveries about the nature of the child and his developmental needs. These discoveries pushed her to articulate a new philosophy of education and to tirelessly advocate for the child’s rights.

This philosophy championed the role of the child in his own development and celebrated his goal of achieving independence. She defined a new purpose of education that would seek to aid a child in his quest while removing the obstacles that had previously hindered him. She called on adults, whether educators or parents, to learn the true nature of the child, to observe him carefully, and to take up the mantle in their proper role as helpers on the child’s journey to competence and self-creation.

Stay tuned for upcoming articles discussing the characteristic materials and methods used in her schools and Montessori’s advice for parents.

If that’s something that interests you, please feel free to subscribe so you won’t miss any new posts.

Montessori, Maria. The Absorbent Mind (Unabridged Start Publishing LLC) (p. 19). Start Publishing LLC. Kindle Edition.

Montessori, Maria. The Absorbent Mind (Unabridged Start Publishing LLC) (p. 133). Start Publishing LLC. Kindle Edition.

Montessori, Maria. The Absorbent Mind (Unabridged Start Publishing LLC) (p. 135). Start Publishing LLC. Kindle Edition.

Montessori, Maria. The 1946 London Lectures (Montessori series Book 17) (p. 28). Montessori-Pierson Publishing House. Kindle Edition.

Montessori, Maria. The Secret of Childhood (Montessori series Book 22) (p. 30). Kindle Edition.

Montessori, Maria. The Absorbent Mind (Unabridged Start Publishing LLC) (p. 77). Start Publishing LLC. Kindle Edition.

Montessori, Maria. The Absorbent Mind (Unabridged Start Publishing LLC) (p. 20). Start Publishing LLC. Kindle Edition.

Montessori, Maria. Spontaneous Activity in Education (p. 97). . Kindle Edition.

Montessori, Maria. Spontaneous Activity in Education (pp. 164-165). . Kindle Edition.